Allocating Memory for DMA in Linux

Allocating Memory for DMA in Linux

In this post we take a look at allocating memory on Linux using huge pages with the intention of sharing that memory with PCIe devices that use DMA.

I’ve recently had the pleasure of writing some user-space code that takes control of an Ethernet card – specifically the Intel i350 and it’s kin. Part of the interface with the device requires sharing memory that contains packet descriptors and buffers. The device uses this memory for the communication of transmitted and received Ethernet packets.

When writing a user-space program that shares memory with a hardware device, we need to make sure that the memory is both accessible to hardware and respected by the operating system.

To begin to understand this requires us to be notionally aware of the manner in which devices will access the memory that we share with them, and how to ask the OS to respect the physical location of the memory.

How Devices Can Access Memory

These days, devices that are connected to a computer are typically connected via PCI Express (usually abbreviate to PCIe). Such devices will typically include support for accessing memory via DMA (Direct Memory Access).

Before the advent of DMA, when a device wanted to write data to memory it would have to interrupt the CPU. The CPU would read data from the PCI device into a register, and then copy the register into memory. This meant that the CPU was interrupted every time that a device wanted to read/write memory. This was less than ideal, especially as the number of devices requiring memory access increased.

DMA was introduced to allow devices to directly access system memory without interrupting the processor. In this model, an additional device (called a DMA engine) would handle the details of memory transfers. Later devices (often called Bus Masters) would integrate the DMA functionality locally, obviating the need for a discrete DMA engine.

In this more recent model of PCI, the North Bridge would decode the address and recognize itself as the target of a PCI transaction, and during the data phase of the bus cycle, the data is transferred between the device and the North Bridge, which will in turn issue DRAM bus cycles to communicate with system memory.

The term bus mastering is still used in PCI to enable a device to initiate DMA. It is often still necessary to enable bus mastering on many devices, and the command register in the PCI configuration space includes a flag to enable bus mastering.

When programming a device connected via PCIe, you will typically be writing a base address for a region of memory that you have prepared for the device to access. However, this memory cannot be allocated in the usual way. This is due to the way memory addresses are translated by the MMU and the operating system – the memory that we traditionally allocate from the operating system is virtual.

Virtual and Physical Addresses

Typical memory allocation, such as when we use malloc or new, ultimately uses memory the operating system has reserved for our process. The address that we receive from the OS will be an address in the virtual memory maintained by the OS.

This virtual address is used by our process when accessing memory, and the CPU will translate the virtual address to a physical memory address using the MMU.

Devices that use DMA to access memory will bypass the CPU when accessing memory, as the north bridge will translate certain PCI messages to DRAM cycles directly. As this process does not involve the MMU, no virtual address translation can take place.

This has the consequence that any memory that you allocate using malloc or new will result in a virtual memory address that, if passed as-is to a device, will result in that device attempting to access a completely different region of memory to the physical location(s) associated with the virtual address. As the CPU is no longer involved in the process, there is little to no protection against devices accessing arbitrary areas of system memory. This can have many unintended consequences – ranging from overwriting important areas of memory all the way to full-blown exfiltration of secrets. Which is nice.

It is important, therefore, that for any allocated memory we are able to obtain the corresponding physical memory address. However, this process is somewhat frustrated by the manner in which memory will be allocated by the operating system. There are a few things that need to be considered:

- Contiguous virtual memory is rarely physically contiguous (except perhaps when the machine boots or in small amounts).

- The operating system is free to swap out pages of memory, such as when a process is considered idle or when the system is under memory pressure.

In order to address these two primary concerns we need to look to an alternative means of memory allocation than the traditional malloc and new. Moreover, as we are likely to need more than a standard page’s worth of space (typically 4Kib), we need to allocate memory using larger pages of memory.

Establishing Physical Addresses

We understand that a process operates on virtual memory, and that memory is arranged in pages. The question now arises as to how we can establish the corresponding physical address for any given virtual address.

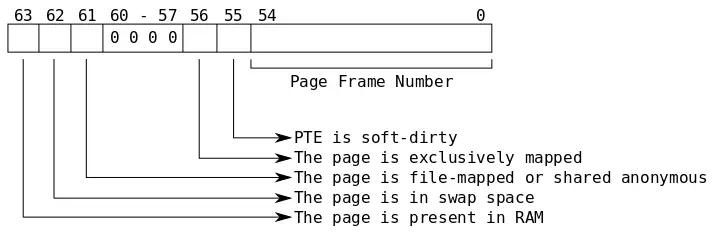

An answer to this lies in the process page map. The page map is a table that provides a correspondence between a virtual page number and the physical address of that page, along with some flags that tell us information about the page’s residency. Each entry in the table is a 64-bit value, with bits 63 down through 55 providing the various flags, and bits 54 to 0 giving the page frame number (assuming the page is in RAM).

Note that bits 54 through 0 are only the physical page frame number if the page is currently in memory. Under other circumstances it can indicate such things as the swap type and offset. We can ascertain whether the page is actually in RAM by checking if bit 63 is set. If bit 63 is set then the bits 54 through 0 are the page frame number.

The page map is found under the /proc sub-directory for each process. A process is able to access this table by opening the /proc/self/pagemap file.

int fd = open("/proc/self/pagemap", O_RDONLY);

assert(fd != -1);

Given a virtual address, we need to calculate the page in which the address resides. In order to do so we need to know the size of a page. Typically this will be 4Kib, but it is possible it may vary on different architectures. We can obtain the page size by using the sysconf function and querying the _SC_PAGESIZE. Given this page size we can then simply divide the virtual address (as a uintptr_t) by the page size to get the virtual page number.

Once we have the virtual page number we can look up our virtual page in the page map. Each entry in the page map is a 64-bit integer, so we need to multiply our virtual page number by eight to find the corresponding entry for the virtual address.

int res = lseek64(fd,

(uintptr_t)vaddr / page_size * sizeof(uintptr_t),

SEEK_SET);

assert(res != -1);

With the file handle in fd pointing to the correct location in the page map, we can read the 64-bit integer at that address. We will read this into a uintptr_t, after which we can close the file.

uintptr_t phy = 0;

res = read(fd, &phy, sizeof(uintptr_t));

assert(res == sizeof(uintptr_t));

close(fd);

Now that we’ve read the entry from the page map we can first check to make sure that the address is actually present in RAM. Consulting our flags we see that bit 63 must be set for this to be the case.

assert((phy & BIT(63)) != 0);

Now we can compute the physical address. The value given in the lower 55 bits of phy is the page frame number. The physical memory is divided into contiguous regions of the system page size, thus we can multiply the page frame number by the system page size to obtain the physical address.

physical_address = PFN * page_size

To make our virtual to physical mapping complete, we should take into account the case where our virtual address is offset from the start of a page. Therefore we need to make sure to add that offset to the computed physical address. The offset from the start of the page to the virtual pointer can be obtained by taking the modulus with the system page size. We can then add this on to our computed physical address.

physical_address = PFN * page_size + (vaddr % page_size)

Putting this all together we get a function virtual_to_physical that maps an address in the virtual address space of the process to a physical address.

static uintptr_t virtual_to_physical(const void *vaddr) {

auto page_size = sysconf(_SC_PAGESIZE);

int fd = open("/proc/self/pagemap", O_RDONLY);

assert(fd != -1);

int res = ::lseek64(fd, (uintptr_t)vaddr / page_size * sizeof(uintptr_t), SEEK_SET);

assert(res != -1);

uintptr_t phy = 0;

res = read(fd, &phy, sizeof(uintptr_t));

assert(res == sizeof(uintptr_t));

close(fd);

assert((phy & BIT(63)) != 0);

return (phy & 0x7fffffffffffffULL) * page_size

+ (uintptr_t)vaddr % page_size;

}

We can now use the virtual_to_physical function to ascertain the physical address of some memory that we allocate from the operating system. This is the address that we pass on to our hardware.

Linux Huge Pages

Now we know how to establish the physical address corresponding to a virtual address, the problem still remains that we need to obtain an address for contiguous physical memory, rather than merely the physical address of a single page. We are also still limited by the fact that the operating system may subject our memory to swapping and other operations.

The Linux operating system provides a facility to allocate memory in pages that are larger than 4Kib in size: huge pages. These huge pages are also treated somewhat differently than normal process memory.

Linux includes support for something called hugetlbpage, which provides access to larger page sizes supported by modern processors. Typically an x86 processor will support pages of 4Kib and 2Mib, and sometimes 1Gib.

Allocated huge pages are reserved by the Linux kernel in a huge page pool. These pages will be pre-allocated, and cannot be swapped out when the system is under memory pressure. The reservation of these huge pages depends on the availability of physically contiguous memory in the system. The kernel is typically instructed to arrange huge page reservation in two ways:

- Configured on boot by specifying the

hugepages=Nparameter in the kernel boot command line, or - Dynamically by writing to

/proc/sys/vm/nr_hugepages, or - Dynamically by writing to the corresponding

nr_hugepagesfile for the NUMA node.

For example, the number of 2Mib huge pages reserved under NUMA node 0 is found in the file at the following location:

/sys/devices/system/node/node0/hugepages/hugepages-2048kB/nr_hugepages

Writing to this file will dynamically change the number of huge pages allocated for the corresponding NUMA node. For example, to allocate 32 2Mib huge pages per NUMA node on a system with 8 NUMA nodes you could run the following shell script:

NUMA_DIR="/sys/devices/system/node"

HUGEPAGE_DIR="hugepages/hugepages-2048kB"

for i in {0..7}; do

echo 32 > $NUMA_DIR/node$i/$HUGEPAGE_DIR/nr_hugepages

done

Something to note is that the kernel will try and balance the huge page pool over all NUMA nodes. Moreover, if the reservation of physically contiguous memory under a subset of NUMA nodes is unsuccessful, the kernel may try and complete the reservation by allocating the extra pages on other nodes. This can result in some bottlenecks when you assume all your huge pages are resident on the same NUMA set.

Huge pages provide a rather nice solution to our problem of obtaining large contiguous regions of memory that are not going to be swapped out by the operating system.

Establishing Huge Page Availability

The first step towards allocating huge pages is to establish what huge pages are available to us. To do so we’re going to query some files in the /sys/kernel/mm/hugepages directory. If any huge pages are configured, this directory will contain sub-directories for each huge page size:

$ ls /sys/kernel/mm/hugepages

hugepages-1048576kB hugepages-2048kB

Each huge page directory contains a number of files that yield information about the number of reserved huge pages in the pool, the free count, and so on:

$ tree /sys/kernel/mm/hugepages

/sys/kernel/mm/hugepages/

├── hugepages-1048576kB

│ ├── free_hugepages

│ ├── nr_hugepages

│ ├── nr_hugepages_mempolicy

│ ├── nr_overcommit_hugepages

│ ├── resv_hugepages

│ └── surplus_hugepages

└── hugepages-2048kB

├── free_hugepages

├── nr_hugepages

├── nr_hugepages_mempolicy

├── nr_overcommit_hugepages

├── resv_hugepages

└── surplus_hugepages

A quick summary of each of these files is given below, and a more precise description can be found in the hugetlbpage.txt documentation.

free_hugepages– The number of huge pages in the pool that are not yet allocated.nr_hugepages– The number of persistent huge pages in the pool. These are huge pages that, when freed, will be returned to the pool.nr_hugepages_mempolicy– Whether to allocate huge pages via the/procor/sysinterface.nr_overcommit_hugepages– The maximum number of surplus hugepages.resv_hugepages– The number of huge pages the OS has committed to reserve, but not yet completed allocation.surplus_hugepages– Number of surplus huge pages that are in the pool above that given innr_hugepages, limited bynr_overcommit_hugepages.

You can use these files to establish information such as whether an allocation will succeed based on the number of available huge pages given in free_hugepages. For the sake of simplicity, as we’re only really concerned with the process of allocating these huge pages, I’m going to ignore them in this post.

In order for our program to comprehend the available huge pages we’ll load some information from the /sys/kernel/mm/hugepages directory and encapsulate it in a HugePageInfo structure.

namespace fs = std::experimental::file_system;

struct HugePageInfo {

std::size_t size; // The size of the hugepage (in bytes)

HugePageInfo(const fs::directory_entry &);

// Allocate a huge page in this pool

HugePage::Ref allocate() const;

// Load all the available huge page pools

static std::vector<HugePageInfo> load();

};

The structure retains the size of the huge page in bytes along with the path to the mount point of the hugetlbfs into which we should create our files for allocation.

When we construct a HugePageInfo structure we pass in a directory_entry that represents the sub-directory under /sys/kernel/mm/hugepages. This sub-directory will have a name that includes the size of the huge-pages that can be allocated within that huge page table. We’ll use a regular expression to extract the page size from the directory name before we parse it.

static const std::regex HUGEPAGE_RE{"hugepages-([0-9]+[kKmMgG])[bB]"};

HugePageInfo::HugePageInfo(const fs::directory_entry &entry) {

// Extract the size of the hugepage from the directory name

std::smatch match;

if (std::regex_match(entry.path().filename(), match, HUGEPAGE_RE)) {

size = parse_suffixed_size(match[1].str());

} else {

throw std::runtime_error("Unable to parse hugepage name");

}

}

To load all the available huge pages we can scan the /sys/kernel/mm/hugepages directory and construct a HugePageInfo instance for each sub-directory. This task is performed by the HugePageInfo::load method.

static const fs::path SYS_HUGEPAGE_DIR = "/sys/kernel/mm/hugepages";

std::vector<HugePageInfo> HugePageInfo::load() {

std::vector<HugePageInfo> huge_pages;

for (auto &entry : fs::directory_iterator(SYS_HUGEPAGE_DIR)) {

huge_pages.emplace_back(entry);

}

return huge_pages;

}

Allocating a Huge Page

Each huge page allocation is described by a HugePage structure. This structure encapsulates the virtual and physical address of an allocated huge page along with the size of the page in bytes.

struct HugePage {

using Ref = std::shared_ptr<HugePage>;

void * virt;

uintptr_t phy;

std::size_t size;

HugePage(void *v, uintptr_t p, std::size_t sz)

: virt(v), phy(p), size(sz) {

}

~HugePage();

};

To allocate a huge page we want to use the mmap system call with the MAP_HUGETLB flag. If we did not use the MAP_HUGEPAGE flag then we would need to mount a hugetlbfs of the required size into a directory somewhere and create files within that file system. We would rather avoid this method, so we use MAP_HUGETLB instead.

As we are not backing this mapping with a file, we need to use the MAP_ANONYMOUS flag. A portable application making use of MAP_ANONYMOUS should set the file descriptor to -1 and pass zero as the offset.

HugePage::Ref HugePageInfo::allocate() const {

// Map a hugepage into memory

void *vaddr = (void *)mmap(NULL, size,

PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE,

MAP_PRIVATE | MAP_ANONYMOUS | MAP_HUGETLB,

-1, 0);

assert(vaddr != MAP_FAILED);

return std::make_shared<HugePage>(vaddr, virtual_to_physical(vaddr), size);

}

The value that we return from allocate constructs a HugePage with the virtual address that we received from mmap, the equivalent physical address as calculated by our virtual_to_physical function and the size of the huge page.

Deallocating a Hugepage

Once we no longer wish to retain a huge page we need to release it back into the huge page pool maintained by the operating system.

The HugePage destructor will use the munmap syscall to un-map the huge page from the process.

HugePage::~HugePage() {

int rc = munmap(virt, size);

assert(rc != -1);

}

Dividing Up a Hugepage into Buffers

Note: If you only wanted to know about the allocation of huge pages then you can skip to the conclusion.

When writing the interface with the Ethernet card, I needed to be able to ensure that each huge page was carved up into a number of fixed size buffers. Moreover, these buffers had specific alignment considerations that could vary by device. To facilitate this, I laid out all the buffers in a huge page as follows:

A ◀─╴size╶─▶ B ◀─╴size╶─▶ ◀─╴size╶─▶

┌─────┬───┬───┬─────┬───┬─────┬───┬──────────┬───┬──────────┬─────┬──────────┐

│ C │ H │ H │ … │ H │ … │▒▒▒│ Buffer 0 │░░░│ Buffer 1 │ … │ Buffer n │

└─────┴───┴───┴─────┴───┴─────┴───┴──────────┴───┴──────────┴─────┴──────────┘

│ │ │ ▲ ▲ ▲

└───┼─────────┼────────────┘ │ │

└─────────┼───────────────────────────┘ │

└────────────────────────────────────────────┘

At the start of the huge page, denoted by the letter C, is a small “chunk” header that describes the contents of the huge page. Immediately after the chunk header are a series of buffer headers, denoted by the letter H. These headers contain information about each buffer.

There are two kinds of padding in this diagram:

- The first kind of padding, denoted by the letter

A, is the padding between the end of the buffer headers and the first buffer in the page. This ensures the first buffer is positioned at the required alignment. - The second kind of padding, denoted by the letter

B, is the inter-buffer padding. This padding ensures that each subsequent buffer is aligned as required.

Each huge page starts with a Chunk structure describing the buffers that are contained in the page. This structure retains the HugePage::Ref that we receive from the HugePageInfo::allocate() function, along with the size of the buffers and a pointer to the first buffer header. The Chunk structure is padded to a multiple of 64 bytes to ease alignment.

struct Chunk {

HugePage::Ref dma;

std::size_t buf_size;

Buffer * first_buffer;

Chunk * next;

uint32_t padding[2];

};

// Make sure our chunk header size is a multiple of 64 bytes

static_assert(sizeof(Chunk) % 64 == 0);

The Buffer structure describes the buffer header, and contains various information about the contents of the buffer. Again, this header is padded to a multiple of 64 bytes.

struct Buffer {

void *address; // Virtual address of the buffer data

uint64_t phy; // Physical address of the buffer data

std::size_t size; // Size of the buffer

Buffer * next; // Next buffer in list (used for free list)

// Other data fields such as packet length, RSS hash and so on

// can be added here, so long as 'padding' is adjusted accordingly.

uint32_t padding[8];

};

// Make sure the buffer header is a multiple of 64 bytes

static_assert(sizeof(Buffer) % 64 == 0);

In order to divide up a huge page we will need to populate the Chunk header at the start of the page, followed by the Buffer headers. This means we need to know:

- The offset to the first buffer in the chunk,

- The amount of slop (spilled space) between the chunk header and the first buffer,

- The amount of buffer slop, being the interstitial padding between each buffer to maintain alignment,

- The number of buffers that we can fit into the huge page.

To calculate this we use a structure called ChunkLayout which takes the parameters for our huge page and buffers and computes the best alignment and packing of the data.

struct Layout {

// Our arguments/input variables

std::size_t buffer_size;

std::size_t alignment;

std::size_t nbuffers;

// Computed layout information

uint64_t chunk_header_size{0};

uint64_t buffer0_offset{0};

uint64_t chunk_slop{0};

uint64_t buffer_slop{0};

uint64_t chunk_space{0};

Layout(std::size_t size,

std::size_t align,

std::size_t page_size) {

buffer_size = size;

alignment = align;

nbuffers = 1;

optimize(page_size);

}

private:

// Compute the layout information for a given number of buffers

void compute(std::size_t n);

// Try and find a "best fit" buffer count

void optimize(std::size_t page_size);

};

To compute the layout, we first need to ascertain the chunk header size, which we can do by adding the size of the Chunk structure to the size of the Buffer structure, multiplied by the number of buffers in the page.

void Layout::compute(std::size_t n) {

nbuffers = n;

// Calculate the chunk header size (C + n * H)

chunk_header_size = sizeof(Chunk) + sizeof(Buffer) * n;

Next we want to calculate the offset from the end of the chunk headers to the first buffer. This uses an align_to template that simply rounds up a value until it’s a multiple of an alignment. We round up the size of the combined chunk header until it meets the requested buffer alignment, giving us the offset into the huge page of the first buffer.

buffer0_offset = align_to<uint64_t>(chunk_header_size, alignment);

Now we need to know the amount of space between the first buffer and the end of the chunk header, which we can easily obtain by just subtracting the chunk header size from the offset of the first buffer.

chunk_slop = buffer0_offset - chunk_header_size;

Now we need to work out the amount of interstitial space between each buffer. This is relevant, as there may be cases where the size of a buffer may not adhere to it’s own address alignment. The interstitial buffer space is simply the modulus of the buffer size and the requested buffer alignment.

buffer_slop = buffer_size % alignment;

Finally we can calculate the amount of space that we use for this chunk. This is the total space, including:

- The size of the combined chunk header (made of one

Chunkstructure and one or moreBufferstructures), - The slop before the first buffer,

- The slop between the buffers, and

- The buffer data itself.

// Start off with the chunk header and slop.

chunk_space = chunk_header_size + chunk_slop;

// Add on the buffer data, where 'n' is the number of buffers.

chunk_space += n * buffer_size;

// Now accommodate the interstital slop. Bear in mind

// that there is N-1 interstitials for N buffers.

chunk_space += (n - 1) * buffer_slop;

}

Now we’ve calculated the amount of space we’ll use for a given buffer size, alignment and number of buffers. We can move on to optimizing the number of buffers to make full use of a huge page.

To optimize the number of buffers we want to add buffers to the layout, until we get to an ideal configuration. We’ll know when we’ve reached saturation when the amount of space remaining exceeds the size of a huge page.

void Layout::optimize(std::size_t page_size) {

std::size_t current_nbuffers = nbuffers;

std::size_t last_nbuffers = current_nbuffers;

for (;;) {

The first thing we want to do is perform our layout calculation for the current number of buffers that we are testing:

// Compute the sizes of the chunk layout for the number of

// buffers in 'current_nbuffers'.

compute(current_nbuffers);

Now we’ve calculated the size of the required space for current_nbuffers buffers, which is given in the chunk_space field. We check to see if this exceeds the size of a page. If it does, we terminate our search. If it does not, we increment the number of buffers and continue.

if (chunk_space > page_size) {

break;

}

last_nbuffers = current_nbuffers;

++current_nbuffers;

}

After the for loop we are going to be in one of two conditions:

- The

last_nbuffersvariable contains the last number of buffers that fit within the given page size, or - We couldn’t even fit one buffer in.

To finish off the optimisation of the layout we will first run a calculation of the layout for the last_nbuffers value, and then check to make sure we actually fit within the page. If we did not fit, then our page is too small for the required buffer size and alignment.

compute(last_nbuffers);

if (chunk_space > page_size) {

throw std::runtime_error("Page cannot accommodate buffers");

}

}

Now that we are able to calculate the layout of a series of identically sized buffers, we can build a class DMAPool that will set up and manage all the buffers for us. This class has a couple of goals:

- Given a

HugePageInfo, required buffer size and alignment, compute the layout using theLayoutstructure. - Provide an interface for allocating and deallocating buffers from the

DMAPool, where the pool allocates a newHugePageAllocwhen the available buffers are exhausted.

The DMAPool class keeps track of a list of free buffers by linking together the Buffer::next fields into a single linked list. This forms a free list from which buffers can be allocated. When we exhaust this list, the DMAPool will request a new HugePageAlloc from it’s HugePageInfo, set up all the Buffer headers and chain them onto the free list.

class DMAPool {

const HugePageInfo *_huge_page;

Layout _layout;

Chunk * _first_chunk{nullptr};

Buffer * _free_list{nullptr};

void new_chunk();

public:

DMAPool(const HugePageInfo *hp,

std::size_t buffer_size,

std::size_t alignment)

: _huge_page(hp), _layout(buffer_size, alignment, hp->size) {

}

~DMAPool();

Buffer *allocate();

void free(Buffer *);

};

The first function we should consider is the DMAPool::new_chunk method. This method will allocate a new HugePageAlloc from the HugePageInfo and carve it up into the required number of buffers.

void DMAPool::new_chunk() {

// Allocate a huge page

auto page = _huge_page->allocate();

// We need to move around by bytes from the start of the virtual

// address of the huge page. We'll create a 'start' pointer for

// this process.

uint8_t *start = (uint8_t *)page.virt;

// Our 'Chunk' starts at the virtual address of the page

Chunk *chunk = (Chunk *)start;

// Populate some of the fields of the chunk header

chunk->dma = page;

chunk->buf_size = _layout.buffer_size;

// Get a pointer to the first buffer header in the page

Buffer *buffer = (Buffer *)(start + sizeof(Chunk));

// Set this as the first buffer header in the chunk

chunk->first_buffer = buffer;

// Get a pointer to the first buffer data in the page

uint8_t *buffer_data = start + _layout.buffer0_offset;

Now we need to iterate through the Buffer headers in the chunk and fill in the information. As we go we increment the Buffer pointer as all the buffer headers are contiguous. We increment the buffer_data field by the buffer size, plus the interstitial space from our layout. This preserves the alignment of the buffer data.

After we have populated each Buffer header structure, we chain it onto the front of the free list maintained by the DMAPool class.

for (std::size_t i = 0; i < _layout.nbuffers;

++i, ++buffer,

buffer_data += (_layout.buffer_size + _layout.buffer_slop)) {

// Set the fields of the buffer header

buffer->address = buffer_data;

buffer->phy = page.phy + (buffer_data - start);

buffer->size = _layout.buffer_size;

// Chain this buffer onto the free list

buffer->next = _free_list;

_free_list = buffer;

}

Now that we’ve allocated a new huge page and populated all the buffer headers we can chain the chunk onto our chunk list.

chunk->next = _first_chunk;

_first_chunk = chunk;

}

An important point to note is that we’re computing the physical address of a buffer by adding the offset of the virtual address of the buffer data from the start of the page to the physical address of the page. This is fine when we’re only allocating a single huge page at a time. If this were not the case, we’d need to ensure that we’re calculating the physical address using our virtual_to_physical function defined earlier. This is because, whilst a huge page is physically contiguous, an allocation of two or more huge pages may not be physically contiguous. Put another way, an allocation of two huge pages may not yield two huge pages that are placed physically next to each other.

When we want to allocate a Buffer from the DMAPool we call the DMAPool::allocate method. This will first try and return a Buffer from the head of the buffer free list. If the free list is empty, it will call the DMAPool::new_chunk method to create a new Chunk. This method will also chain all the buffer headers onto the free list. The allocate method may then return a newly allocated buffer.

Buffer *DMAPool::allocate() {

Buffer *buffer = _free_list;

if (!buffer) {

new_chunk();

buffer = _free_list;

}

_free_list = buffer->next;

buffer->next = nullptr;

return buffer;

}

When we want to free a Buffer we simply append it to the free list in the DMAPool.

void DMAPool::free(Buffer *buffer) {

buffer->next = _free_list;

_free_list = buffer;

}

Finally, when we are done with a DMAPool it’s destructor will be called. This destructor needs to free all the HugePageAlloc information in each Chunk.

DMAPool::~DMAPool() {

Chunk *chunk = _first_chunk;

Chunk *next = nullptr;

while (chunk) {

next = chunk->next;

chunk->dma.free();

chunk = next;

}

}

With the DMAPool implemented we can begin to portion out buffers of the required size and alignment to hardware. Hardware will require the physical address of each Buffer we allocate from the pool, which is available in the Buffer::phy field. Our process is also able to access this memory via the pointer in the Buffer::address field.

Conclusion

Preparing memory for use with DMA may seem a bit more complex than necessary. As developers we’re often shielded from the details of memory management by useful abstractions such as those provided by malloc and new. This can mean that we are rarely exposed to the manner in which memory is managed by the operating system and our programs.

I hope that this post may be of some use to those of you that need to communicate memory with devices connected to the PCI bus. You can find the complete listing as a GitHub gist:

Cover image courtesy of Harrison Broadbent (@harrisonbroadbent on unsplash)

Related Posts

Bitmap Tri-Color Marking

In this post I look at a simple tri-color marking implementation that uses bitmap operations to walk the heap.